Ach, wie schön. Europa gedenkt wieder einmal des Friedens. Doch hinter den Kulissen brechen die Institutionen des alten Kontinents zusammen. Der Krieg läuft längst anders. Wir haben nur noch nicht die richtigen Worte dafür gefunden. Ein Essay von CLAUS PÁNDI.

Es ist sehr wahrscheinlich, dass Österreich seine Vorgaben im Umweltschutz nicht erfüllt. Das hat nicht nur Folgen für das Ökosystem. Der Klimawandel verbrennt auch Milliarden Euro.

Bei einem Waldspaziergang entdeckt der JKU Physiker Robert Koeppe einen Baum, der von Pilzen zersetzt wird. Er beginnt zu forschen und findet heraus: Der Pilz kann noch viel mehr.

Wenn es plötzlich eine Methode gibt, mit der Kohlendioxid in Alkohol verwandelt werden kann, muss man aufpassen, nicht ins Boulevardeske zu verfallen. Aber „Die Welt retten in der Vollfett’n“ würde der Forschung der Arbeitsgruppe um Wolfgang Schöfberger vom Institut für Organische Chemie der Johannes Kepler Universität Linz nicht gerecht werden. Deswegen so:

Gentherapie gilt als eine der großen Hoffnungen auf Heilung seltener Krankheiten. Aber sie ist nicht unumstritten. Denn sie mäandert zwischen medizinischem Fortschritt, Grenzüberschreitungen und ethischen Herausforderungen. Eine Annäherung in drei Teilen.

Der chinesische Konzern Huawei will in Europa das schnelle 5G-Mobilnetz aufbauen. Doch nicht alle fühlen sich damit besonders wohl. Vielleicht sogar aus gutem Grund.

Die Lernsoftware GeoGebra hat Millionen Userinnen und Usern gezeigt, dass Mathematik vielleicht doch nicht so schlimm ist. Entwickelt hat sie Markus Hohenwarter von der Kepler Universität Linz – und es damit geschafft, Mathe zu einem spannenden Experiment zu machen. Auch auf dem Smartphone.

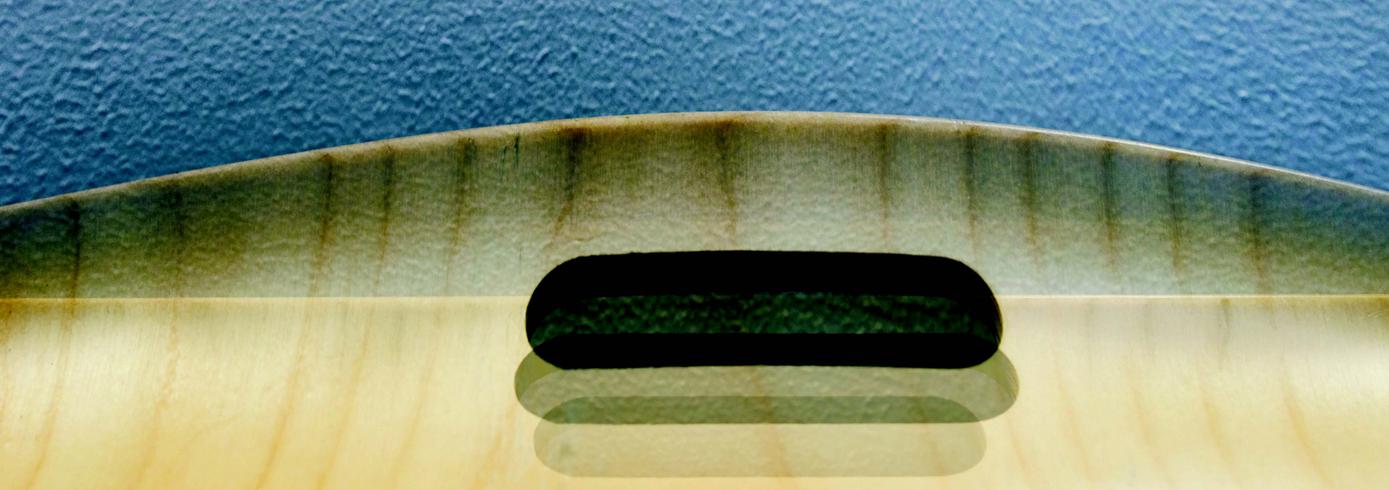

Wenn Martin Schagerl über Gewichtsprobleme nachdenkt, ist seine Lösung nicht einfach „abspecken“. Am Institut für Konstruktiven Leichtbau an der JKU Linz entwickelt er neue Technologien, die Maschinen wie Flugzeuge, Autos oder sogar Windräder leichter und damit effizienter machen. Vorbild ist dabei nicht selten die Natur.

Das Wissenschaftsmagazin „Nature“ ist die weltweit wichtigste Fachpublikation im Gebiet der Naturwissenschaften. Von rund 100.000 eingereichten Studien werden jedes Jahr im Bereich Physik nur rund 40 veröffentlicht. Zwei davon stammen von Physikern der JKU Linz.

Wissenschaft und Kunst stellen zwei Seiten derselben Medaille dar, wenn es darum geht, der Realität hinter den Vorhang zu schauen. Oder wie es in Anlehnung an Goethes Faust im Manifest „Innovation durch Universitas“ heißt: des Pudels Kern zu ergründen. In diesem Manifest, das von den beiden Rektoren Meinhard Lukas und Gerald Bast in der letzten Ausgabe der Kepler Tribune veröff entlicht wurde, wird folgerichtig eine enge Kooperation zwischen WissenschaftlerInnen und KünstlerInnen vorgeschlagen und dafür eine gemeinsame Sprache gefordert. Wir halten es aber für unzureichend, miteinander sprechen zu können. Denn wie alle HundehalterInnen wissen, lässt sich des Pudels Kern nicht beschreiben oder erklären, sondern nur gemeinsam erfahren. Kunst und Wissenschaft müssen daher einen Weg der Zusammenarbeit fi nden, wie diese Erfahrungen gemeinsam erlebt werden können. Wissenschaft und Kunst haben dabei einen natürlichen und ungemein kraftvollen gemeinsamen Dreh- und Angelpunkt, an dem es anzusetzen gilt: Emotionen.

Wir spüren unsere Gedanken und rationalisieren unsere Gefühle. Aus diesem Gemenge entstehen Emotionen. Ebenso wie Ideen teilen wir Emotionen mit unseren Mitmenschen und diese mit uns. Kunst entfaltet ihre Wirkung, wenn sie uns emotional berührt. Das gelingt durch Unmittelbarkeit. Auch wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse haben Impact, wenn sie uns emotional bewegen. Das gelingt mittelbar durch Glaubwürdigkeit der Methode und der ForscherInnen. Emotionen sind nicht nur wesentliche Motivation zu forschen und künstlerisch tätig zu sein, If ever there was a word that could encapsulate the idea of the ‘emperor’s new clothes’, it would be innovation. From its use as a rather mundane term in 13th century legal texts to describing vagabonds jailed for attempting to rewrite religious texts, innovation has certainly managed to punch above its weight ever since. After a shaky start, the term managed to replace invention during the latter half of the 20th century, becoming a global buzzword used to describe any form of change and creativity, irrespective of whether or not it was practised. What was once our word, has become ‘the word’. And that’s when things started going wrong. Together with Lee Vinsel, Andrew Russell penned: “Entire societies have come to talk about innovation as if it were an inherently desirable value, like love, fraternity, courage, beauty, dignity, or responsibility. Innovation-speak worships at the altar of change, but it rarely asks who benefi ts, to what end?” as part of their notable essay ‘Hail the Maintainers’ [Published in Aeon Magazine, 07th of April, 2016: Russell/Vinsel: Hail the Maintainers]. During the last decade at my own business leading a design company and speaking at numerous technology and business conferences, I have observed the hollow promise of innovation by organisations and businesses that consistently fail to deliver in practice. The other reason I am critical and wary of using the term ‘innovation’ is that it has become associated with a brazen desire for infi nite progress and unconstrained economic growth which, in a world of fi nite resources, no longer feels viable. Innovate, or move fast and break things, because the consequences will take care of themselves, has been the rallying cry in Silicon Valley. I wonder if this naive, wilful outcast sondern sie sind letztlich auch das Ergebnis dieser Bemühungen.

Begeisterung und Angst, Liebe und Verzweifl ung – Emotionen beeinfl ussen unsere Entscheidungen und unser Handeln. Kaum jemand denkt oder handelt anders, nur weil wissenschaftliche Fakten vorliegen, selbst wenn sie methodisch noch so sauber erarbeitet wurden. Ebenso wenig ändert sich, wenn technisch und konzeptionell herausragende Kunst geschaffen wird, die aber niemanden berührt. Der gemeinsame Schlüssel zur Wirksamkeit von Kunst und Wissenschaft sind Emotionen.

Für ein Ineinandergreifen von Wissenschaft und Kunst wird man sich also gegenseitig als InteraktionspartnerInnen begreifen müssen. In der Interaktion entstehen gemeinsame Emotionen und damit die Basis für einen gemeinsamen Blick hinter den Vorhang, der ForscherInnen und KünstlerInnen seit jeher fasziniert, an dem sie in Zukunft hoff entlich gemeinsam produktiv scheitern werden. Denn hinter jedem Vorhang erwartet uns wieder ein rätselhafter Pudel und ein weiterer Vorhang – Fortschritt also.

If ever there was a word that could encapsulate the idea of the ‘emperor’s new clothes’, it would be innovation. From its use as a rather mundane term in 13th century legal texts to describing vagabonds jailed for attempting to rewrite religious texts, innovation has certainly managed to punch above its weight ever since. After a shaky start, the term managed to replace invention during the latter half of the 20th century, becoming a global buzzword used to describe any form of change and creativity, irrespective of whether or not it was practised. What was once our word, has become ‘the word’. And that’s when things started going wrong. Together with Lee Vinsel, Andrew Russell penned: “Entire societies have come to talk about innovation as if it were an inherently desirable value, like love, fraternity, courage, beauty, dignity, or responsibility. Innovation-speak worships at the altar of change, but it rarely asks who benefi ts, to what end?” as part of their notable essay ‘Hail the Maintainers’ [Published in Aeon Magazine, 07th of April, 2016: Russell/Vinsel: Hail the Maintainers].

During the last decade at my own business leading a design company and speaking at numerous technology and business conferences, I have observed the hollow promise of innovation by organisations and businesses that consistently fail to deliver in practice. The other reason I am critical and wary of using the term ‘innovation’ is that it has become associated with a brazen desire for infi nite progress and unconstrained economic growth which, in a world of fi nite resources, no longer feels viable. Innovate, or move fast and break things, because the consequences will take care of themselves, has been the rallying cry in Silicon Valley.

I wonder if this naive, wilful outcast has had its run? What other words could we use instead, and how would that change the way we view our fragile planet? Over the past few years, my own work has focused on climate change and during this process, I have encountered works by multispecies scholars such as Ann L. Tsing who propose new, creative, and endearing ways of living in a world of fi nite resources. I am particularly drawn to the word ‘resurgence’ – the idea of renewing, restoring and regenerating, pulling us away from the seductive delusion of endless growth and drawing us instead towards cyclical forms of nurturing, growing, dying, and renewing.

Tsing’s writings about resurgence in the context of multispecies interdependence is exceptionally urgent: “Disturbances, human and otherwise, knock out multispecies assemblages — yet liveable ecologies come back. After a forest fi re, seedlings sprout in the ashes, and, with time, another forest may grow up in the burn. The regrowing forest is an example of what I am calling resurgence. […] Resurgence is the work of many organisms, negotiating across diff erences, to forge assemblages of multispecies livability in the midst of disturbance. Humans cannot continue their livelihoods on resurgence is particularly obvious in considering hunting and gatherings: If animals and plants do not renew themselves, foragers lose their livelihoods. But, although both scholars and modern farmers are prone to forget this, such dependence is equally insistent for agriculturalists and keepers of animals — and thus, too, all those who live on their products. Farming is impossible without multispecies resurgence. [Tsing: A threat to holocene resurgence is a threat to livability; In: Brightman/Lewis (Eds.): The Anthropology of sustainability, p. 52, New York 2017]

I believe in embracing words and ideas that can help us move beyond our anthropocentric view of the world towards a deeper understanding of our interdependence with other species. This would be the most innovative thing we could do today. It is time for a collective resurgence.

Fate has ordained that the men who went to the moon to explore in peace will stay on the moon to rest in peace.” Diese Sätze musste US-Präsident Richard Nixon im Juli 1969 nicht sagen. Die Mondlandung gelang. Der Text verschwand in den Archiven. Es war nicht passiert, was Nixon im Ernstfall hätte sagen müssen. “These two men are laying down their lives in mankind’s most noble goal: the search for truth and understanding.”

Die Geschichte der Mondlandung ist die Geschichte eines Traums. Vielleicht eines der größten Träume der Menschheit: des Fliegens. Über Grenzen. Des Überwindens. Der Schwerkraft. Der Angst. Von alldem, was wir kennen und wissen. Die Reise ins Weltall ist die Reise ins Ungewisse. So wie die Enterprise in „Galaxien vordringt, die nie zuvor ein Mensch gesehen hat“, versucht jede Wissenschaftlerin oder jeder Wissenschaftler, Dinge zu erforschen, die noch nie zuvor ein Mensch gesehen, gemessen oder verstanden hat.

2024 will die NASA den nächsten bemannten Flug zum Mond machen. Bald darauf zum Mars fliegen. Bei einem Besuch im Kennedy Space Center sprach JKU Professor Oliver Brüggemann mit Captain Wendy Lawrence, viermalige Teilnehmerin an Shuttle-Missionen. „Für einen Raumfahrt-Fan wie mich war es ein eindrucksvolles und grandioses Erlebnis zuzuhören – wie sehr sich Astronautinnen und Astronauten auf ihrer Reise auf die Wissenschaft verlassen. Verlassen müssen. Wie Physik, Chemie und alle naturwissenschaftlichen Studien hier eingesetzt werden, um einen Traum wahr werden zu lassen, um Menschen gesund zurückzubringen. Um Raumfahrt erst möglich zu machen.“

“We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard”, träumte John F. Kennedy 1962, “because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win.” Der Sieg der Reise zum Mond war ein Sieg der Wissenschaft. Und auch für jeden weiteren Schritt wird es Triumphe in der Wissenschaft brauchen.

Die Wissenschaft, darüber kann es keine zwei Meinungen geben, ist eine aufregende Sache. In jeder Ausgabe widmen wir ihr deshalb die letzten Zeilen. Dieses Mal haben wir gemeinsam mit Prof. Oliver Brüggemann vom Institut für Chemie der Polymere über Raumfahrt nachgedacht.

Norbert Trawöger weigert sich, alles verstehen zu müssen, und hat mittlerweile begriffen, dass das Halten von Gleichgewicht nicht erklärbar ist.

Überlegungen zur „Zuvielisation“ und der Rolle der Bildung